Mary

Calyx (CAL-ix) Diebold---her Mama thought "Mary Alice" was too plain,

and she saw calyx in

a book and thought it was some kind of a flower, not a PART of a flower. Mary

Calyx wears blouses and skirts---great wide ones, with plenty of room to get on

and off her bicycle without her slip a-showin'. Her gray Soft-Spots and thin

white anklets can be seen pumping that Schwinn all over town, especially to the

site of any local happenings. She will never learn to drive a car---her nerves

won't allow it. A thick headband holds her wiry browny-gray hair back from her

face, and a big ole stiff turkeytail of it sticks straight out over the tight

elastic at the back of her head.

Mary Asenath Diebold---elder sister of MC---they're the only two children of the only Catholic family in town. MA was forever christened Mersenith from first grade on. Mersenith can drive, ride, shoot or field-dress anything that she can get her hands on. She hopped in the pickup beside her Daddy when she was still in diapers, standing on the seat with her little arms stretched across the back for balance. She's spent more than a few days lying in an icy field, waiting for a flock of mallards to come in for the night. She works at the Mayor's office, moved into a little furnished apartment in the side of Mrs. Crossland's house when she finished her Secretarial Course at the Junior College, and drives a second-hand Accord, which she paid for herself.

Nancy Fred Baxter---named after her Daddy. An only child, she was a jeans-wearing, tree-climbing, horse-riding tomboy---the lone small female in a neighborhood of all boys, as far as the eye could see. She learned to rip and roar with the best of them, standing up in the Saturday movie to cheer on the hero and boo the villains with shouts and flung Sweet Tarts. Her pockets were stuff-sprung from the weight of her Barlow, her spinnin’ top and Prince Albert bagful of marbles. In her teen years, she hid her hands beneath desk or book, embarrassed at the still-prominent calluses from her years of winning everybody’s aggies. And in her grown-up jewelry box, transferred from the childhood pink one which opened to let a tiny ballerina twirl to a halting, jerky rendition of “Fascination,” she still has her two steelies from those marble-shooting days.

Nancy Fred hates her name, but not as much as Oscar Jeniece Overton must--- after four boys and two other girls, and her the baby---they finally named one after Mr. Oscar. Between layin’ a burden that great on a little baby, and his triflin’ ways in general, the consensus of the town women was that Mr. Oscar needed shootin’. But they never let on to Miss Ethel, his wife---she has quite a big enough Cross to Bear.

Anna (pronounced AHH-NNA) Helen Upchurch crochets and collects Precious Moments and Lladro. She started with a pretty little corner cabinet from a yard sale, proudly called it her étagère, and proceeded to fill it with tiny sweet-faced, big-eyed little bits of ceramic. It was the eyes that called her, like beseeching little prisoners peeking out from behind those teacup tears. And every wall in her house has at least one print of a house or church or street, with flower boxes, glowing street lamps, and a golden glow through every window.

Mary Asenath Diebold---elder sister of MC---they're the only two children of the only Catholic family in town. MA was forever christened Mersenith from first grade on. Mersenith can drive, ride, shoot or field-dress anything that she can get her hands on. She hopped in the pickup beside her Daddy when she was still in diapers, standing on the seat with her little arms stretched across the back for balance. She's spent more than a few days lying in an icy field, waiting for a flock of mallards to come in for the night. She works at the Mayor's office, moved into a little furnished apartment in the side of Mrs. Crossland's house when she finished her Secretarial Course at the Junior College, and drives a second-hand Accord, which she paid for herself.

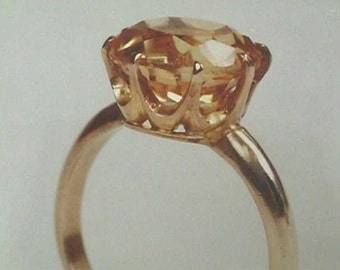

Nancy Fred Baxter---named after her Daddy. An only child, she was a jeans-wearing, tree-climbing, horse-riding tomboy---the lone small female in a neighborhood of all boys, as far as the eye could see. She learned to rip and roar with the best of them, standing up in the Saturday movie to cheer on the hero and boo the villains with shouts and flung Sweet Tarts. Her pockets were stuff-sprung from the weight of her Barlow, her spinnin’ top and Prince Albert bagful of marbles. In her teen years, she hid her hands beneath desk or book, embarrassed at the still-prominent calluses from her years of winning everybody’s aggies. And in her grown-up jewelry box, transferred from the childhood pink one which opened to let a tiny ballerina twirl to a halting, jerky rendition of “Fascination,” she still has her two steelies from those marble-shooting days.

Nancy Fred hates her name, but not as much as Oscar Jeniece Overton must--- after four boys and two other girls, and her the baby---they finally named one after Mr. Oscar. Between layin’ a burden that great on a little baby, and his triflin’ ways in general, the consensus of the town women was that Mr. Oscar needed shootin’. But they never let on to Miss Ethel, his wife---she has quite a big enough Cross to Bear.

Anna (pronounced AHH-NNA) Helen Upchurch crochets and collects Precious Moments and Lladro. She started with a pretty little corner cabinet from a yard sale, proudly called it her étagère, and proceeded to fill it with tiny sweet-faced, big-eyed little bits of ceramic. It was the eyes that called her, like beseeching little prisoners peeking out from behind those teacup tears. And every wall in her house has at least one print of a house or church or street, with flower boxes, glowing street lamps, and a golden glow through every window.